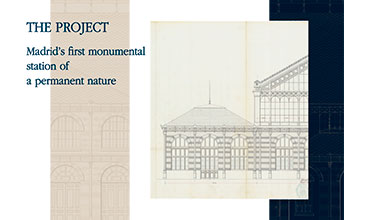

Madrid’s first monumental station of a permanent nature

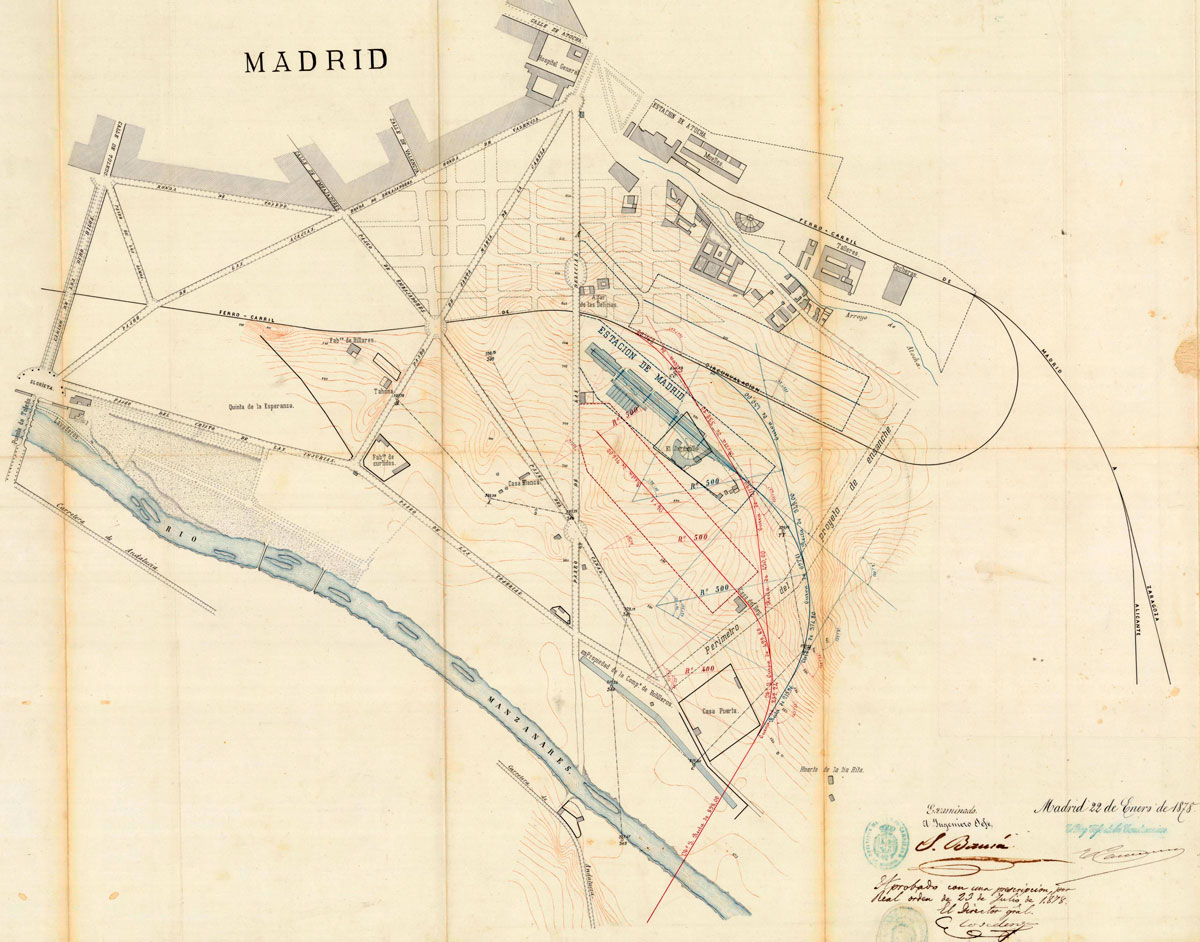

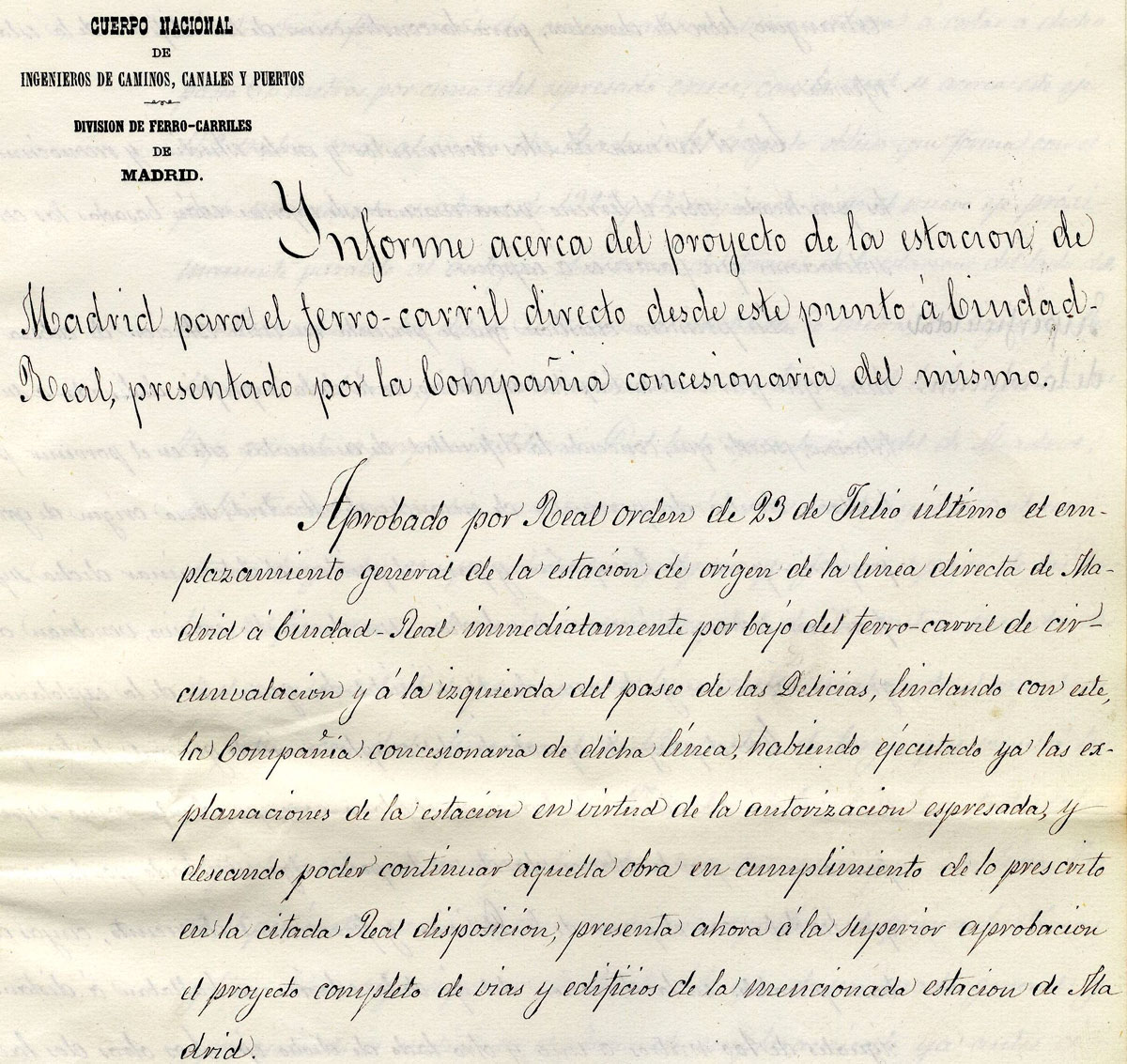

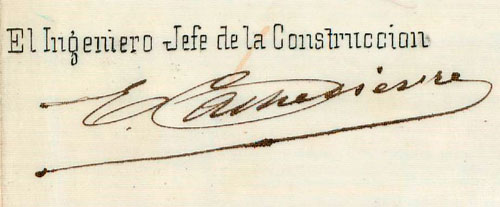

The project was carried out by Émile Cachelièvre, a French civil engineer hired by CRB to build the railway and its terminus station in the capital. The project’s plans, which are kept in the Madrid Railway Museum’s Historical Railway Archive, are dated October 12, 1878, and signed by Cachelièvre as the “Chief Construction Engineer.” He designed a station of a permanent nature, without any prior provisional constructions, as had been the case of Atocha and Príncipe Pío. Functional, rational and extensive (even bigger than some contemporary terminuses in Paris), it would become Madrid’s first monumental station.

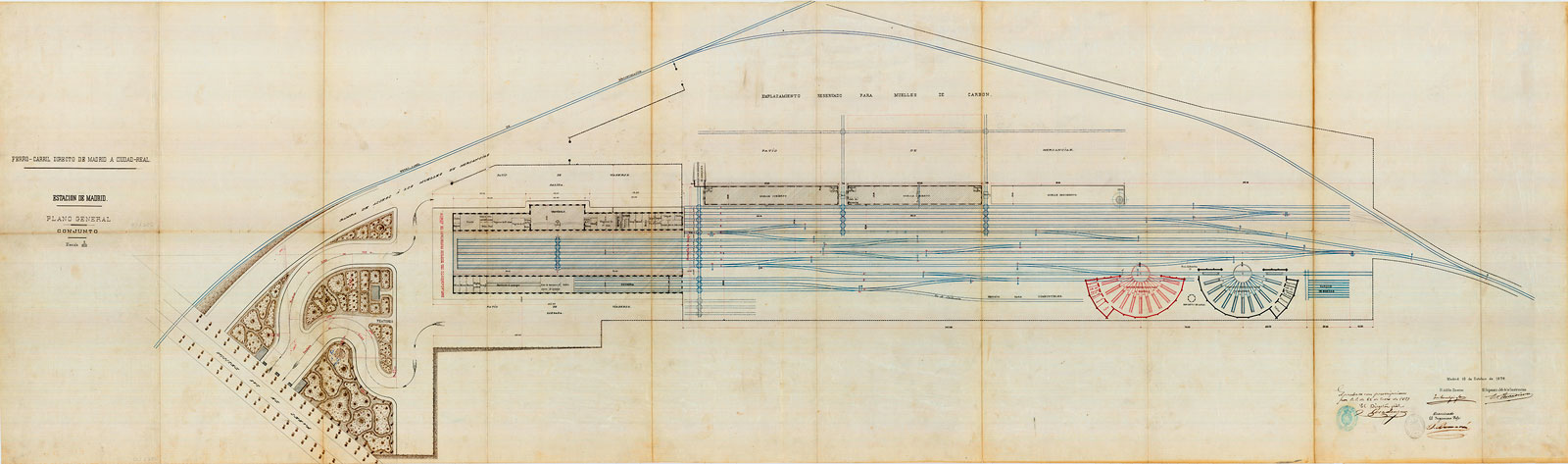

According to the excerpt of the project published in 1879 in the journal Revista de Obras Públicas, the station was equipped with three services (freight, passengers and traction), each with their own installations. Some would be built immediately, and others developed when required by traffic needs.

The freight service would be located in the southeast, beside

the railway ring. It would feature a special, independent road,

with access ramps, a haulage courtyard, covered and open-air

loading bays, others for loading carriages, loading and

unloading tracks, and spare land for different uses.

The traction service was located at the opposite side, 410 m

from the passenger building. It was equipped with two

semi-circular roundhouses, one with thirteen locomotives, which

was to be built immediately, and another with eleven to be built

in the future, if necessary. Both would have a swing bridge, a

pit for cleaning engine boilers, a hydrant and small

outbuildings (workshop, warehouse, personnel offices). It would

also have a hydraulic crane, water deposit, wheels depot, and

service tracks.

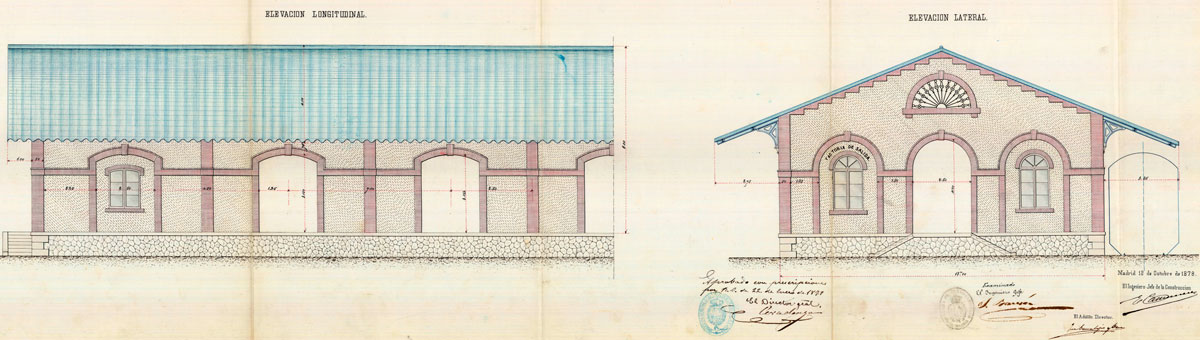

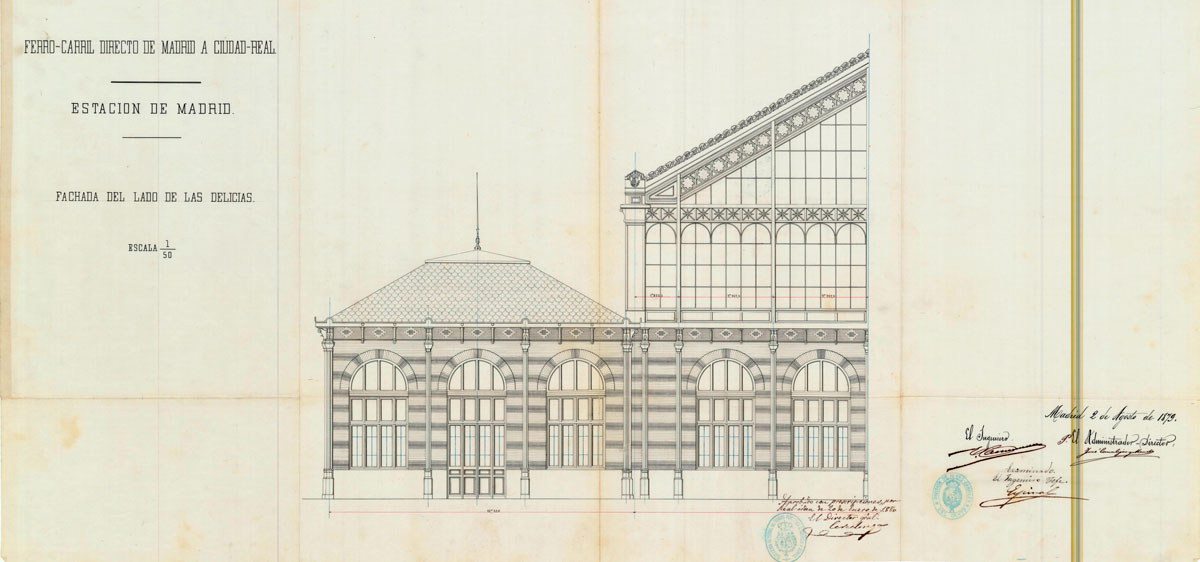

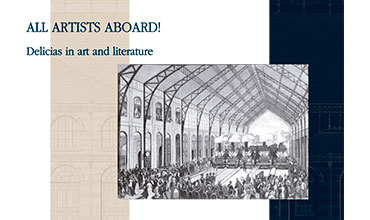

Finally, the passenger service, housed in the main building, was

located in the terminus station. The passenger building,

covering an area of almost 11,000 m², consisted of a simple

ground plan featuring three areas: two parallel side pavilions

(175 m long and 12 m wide), one for passenger departures and

another for passenger arrivals, attached to the central body.

Its typology was closer to that of a way station than a terminus

station, except for the curtain wall at the north façade, which

was used to separate the arrivals and departures traffic. Both

pavilions housed numerous offices, waiting rooms (1st, 2nd and

3rd class), others for distributing luggage, lost luggage and

property, left-luggage, administrative offices, engine shed,

lobbies (with the departures lobby being bigger and more

distinctive than the arrivals one), restaurant, royal lounge,

chandeliers, lamp store, telegraph office, etc. The central body

was designed as a large, diaphanous space (175 m long and 22.5 m

high with a span of 35 m), with five tracks, two platforms,

ventilation lattices and an open lantern-turret at the top, to

let out the smoke from the steam locomotives.

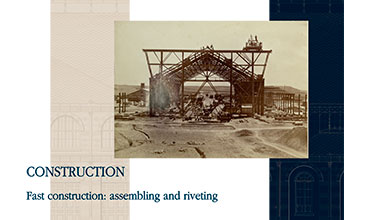

Cachelièvre was highly innovative, which he demonstrated by

designing the building’s framework in iron, a material

considered a symbol of progress, and by applying a construction

technique that was new to Madrid in the last third of the 19th

century. The glass roof was a structure formed by eighteen

trusses or porticos. Each one was attached to a supporting

pillar and the pillars were set into the ground by means of a

sunken foundation. Thus, for the first time in Madrid, an

extensive, diaphanous space was covered without intermediate

supports, crosspieces, braces or bulwarks. This structure was

inspired by the structure that Henry de Dion used in the

Machines Gallery at the Paris World Fair in 1878.

The inspector engineer of the Ministry of Public Works’ Railway

Division, Santiago Bausá, authorised the project on December 2,

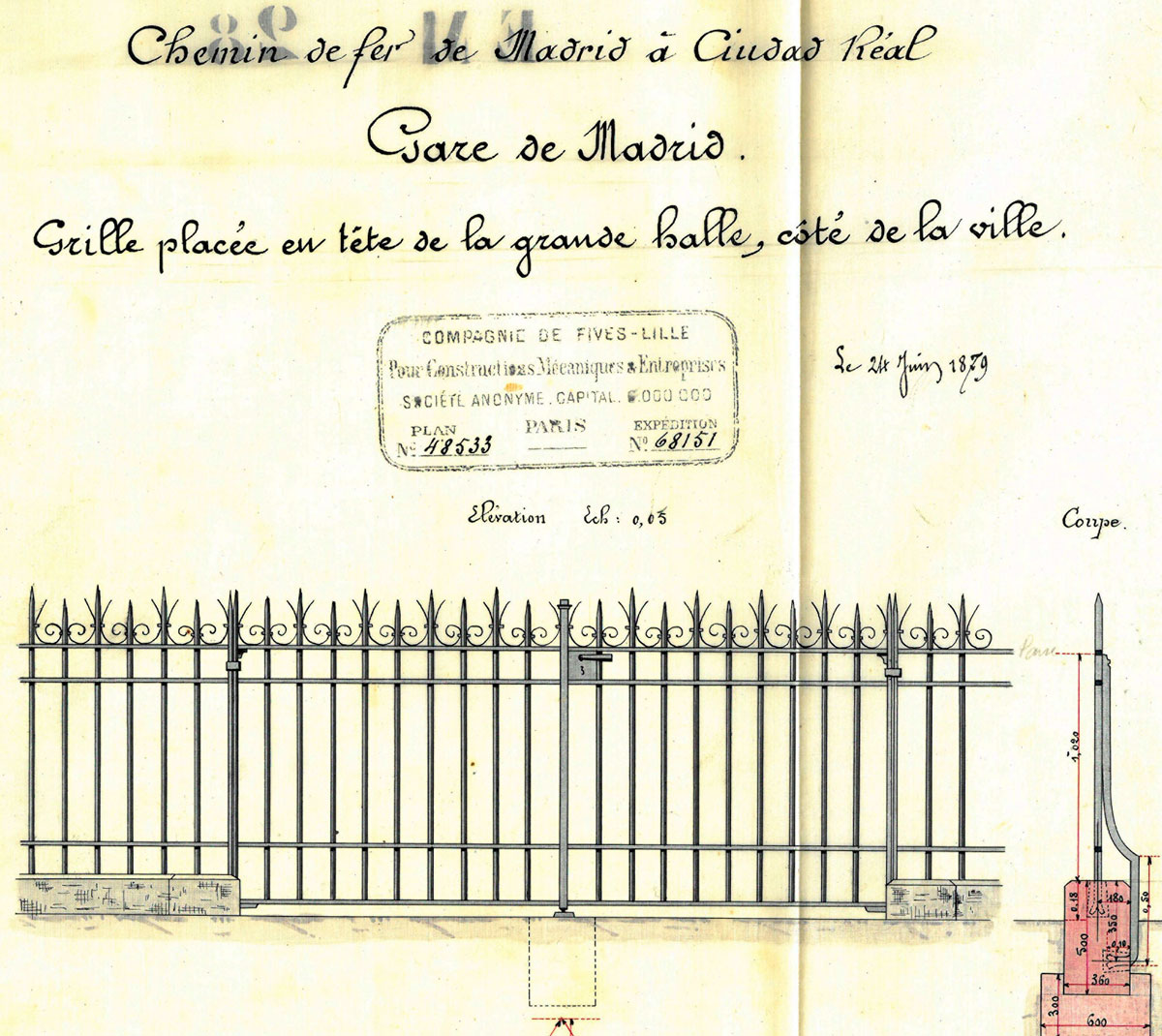

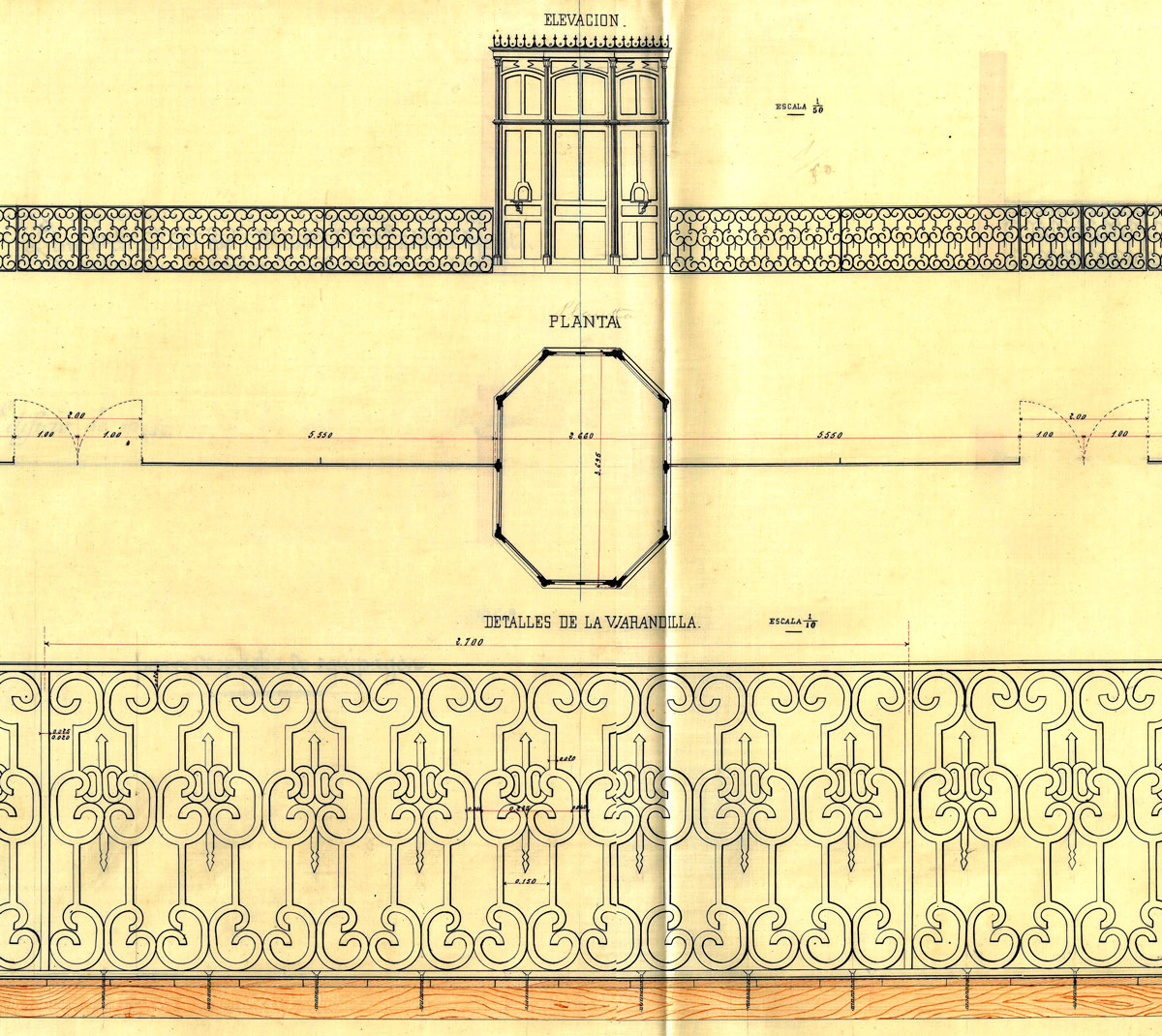

1878. However, for economic reasons, on August 2, 1879, the CRB

company presented a new one with important modifications in the

passenger building. They mainly consisted in eliminating the

administration building at the north façade, replacing it with a

metal gate and garden, rejecting the engine shed and using the

three main tracks as side tracks, making a two-floor division in

several areas of the side pavilions, reducing the central body

to 170 m,

replacing the slate with galvanised roofing iron, etc.

The introduction of these transformations served to balance good

taste with the economy, and the final result was better.

Engineering language with a marked industrial nature triumphed

in the central body, while the architecture of the side

corridors reflected their civil and public function.

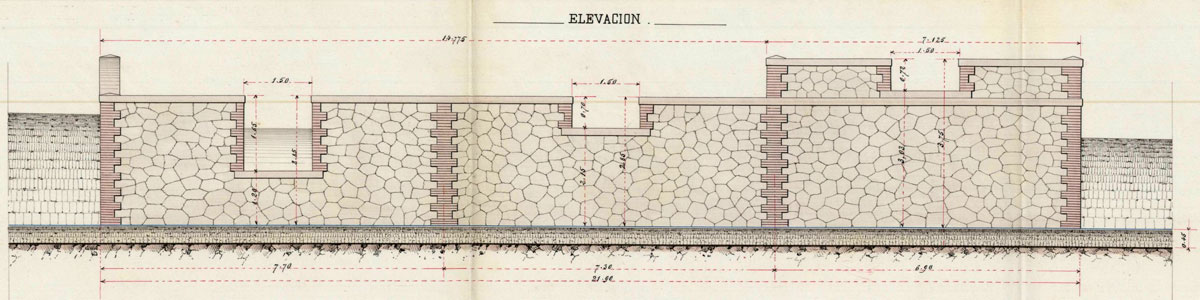

Before Delicias was opened, new projects were drawn up to build

other freight-services installations that would complete the

railway complex, specifically loading bays and deposits.